|

|

At The Picture Show

|

February 2007

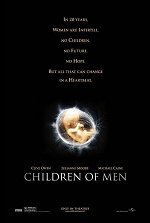

Dystopian messiah

Cuarón re-imagines the future, humanity and sci-fi with the blistering thriller,

'Children of Men'

Children of Men

Universal Pictures

Director: Alfonso Cuarón

Screenplay: Alfonso Cuarón, Timothy Sexton, David Arata, Mark Fergus and

Hawk Ostby, based on the novel by P.D. James

Starring: Clive Owen, Chiwetel Ejiofor, Michael Caine, Julianne Moore, Claire-Hope Ashitey, Pam Ferris, Charlie Hunnam and Peter Mullan

Rated R / 1 hour, 49 minutes

(out of four)

(out of four)

People are already referring to it as "the scene." Without giving anything away, it

takes place in the middle of a chaotic and violent war zone. It is one unbroken

shot, lasting six-and-a-half minutes, that follows our reluctant hero from one

pivotal plot point to another. We are literally put right in the middle of the war

zone, as director Alfonso Cuarón weaves us through it in one of the most

impressive feats of technical virtuosity ever committed to film. The scene -

brilliantly effective in drawing us into the urgency of the moment - is among the

most gripping cinematic moments I've ever experienced. I can honestly say I've

never seen anything quite like it . . . and how often can you say that anymore?

Cuarón's real-time strategy is not only a technical

feat in and of itself, but it capitalizes as a dramatic and emotional payoff. The

scene itself, and the much quieter scene that comes just a few moments later,

clinches Children of Men as the best film of 2006, a genuine masterpiece from a

director who is rapidly becoming one of the best in the field.

Cuarón's real-time strategy is not only a technical

feat in and of itself, but it capitalizes as a dramatic and emotional payoff. The

scene itself, and the much quieter scene that comes just a few moments later,

clinches Children of Men as the best film of 2006, a genuine masterpiece from a

director who is rapidly becoming one of the best in the field.

Even before we get to that key sequence, the film has already separated itself from

the rest of the end-of-the-year rush - and from its own genre. Great films can be

found in all forms and in all genres, but the best are usually those that transcend

that genre. They take the mechanics of the formula to a whole new level, or they

reject the formula altogether and find a new way to tell the story. Children of Men

certainly has a formula, but in the dystopian thriller subgenre, one would be hard-pressed to find anything so fully realized. The "future" in the film is London circa

2027, but it is more concerned with humanity than with differing cultures and

nationalities (though those play a role as well). Humans have become infertile, and

no one can explain why. Society has crumbled, deteriorated into hopeless and

aimless violence that reflects humans' sudden desperation and insignificance and

fear at the prospect of no longer being. It is the near future, but our existence is

bleak.

Even Theo (Clive Owen), a formerly idealistic

political activist, and his eccentric radical friend Jasper (Michael Caine), once a famous political cartoonist, have resigned themselves to the sad fate of

mankind and bought into the depressing cynicism of the day. Perhaps if there were

some glimmer of hope, their eyes would light up, and they would remember why

they're here, and they would remember what it means to fight. But they've seen no

such glimmer in quite some time. "It doesn't matter," Theo says. "It's all over in

50 years."

Even Theo (Clive Owen), a formerly idealistic

political activist, and his eccentric radical friend Jasper (Michael Caine), once a famous political cartoonist, have resigned themselves to the sad fate of

mankind and bought into the depressing cynicism of the day. Perhaps if there were

some glimmer of hope, their eyes would light up, and they would remember why

they're here, and they would remember what it means to fight. But they've seen no

such glimmer in quite some time. "It doesn't matter," Theo says. "It's all over in

50 years."

But then hope does come. And even when Theo sees it - a young woman, Kee

(Claire-Hope Ashitey), pregnant, protected by a radical revolutionary organization

called The Fishes - he at first resists it. He is not the person he once was. But the

group's leader is Theo's militant ex-wife, Julian (Julianne Moore), and he's roped

into protecting Kee before the government or any military organization can step in

and intervene in any way.

Keith Phipps of The Onion AV Club called Children of Men "a heartbreaking,

bullet-strewn valentine to what keeps us human." That is exactly what I wanted to

say upon first seeing the film, only I didn't have the words for it. This is such a

full-fledged experience that it rejects classification; it works so deeply on so many

levels that, in less than two hours, we are drained, physically and emotionally.

Children of Men is full of terrible anguish and

almost-unreachable hope. It is a movie that reaches into us and grabs our insides

and pulls us inside-out. Remember what I said about transcending genre? Children

of Men does just that. This is not just a futuristic drama, this is a universally

human drama. It is not about impressing us with special effects; it is about making

an impact on our souls.

Children of Men is full of terrible anguish and

almost-unreachable hope. It is a movie that reaches into us and grabs our insides

and pulls us inside-out. Remember what I said about transcending genre? Children

of Men does just that. This is not just a futuristic drama, this is a universally

human drama. It is not about impressing us with special effects; it is about making

an impact on our souls.

In fact, when we get to the aforementioned climactic scene in the bullet-riddled

war zone, placed in the middle of frighteningly real action, it's very easy to forget

that any of it is taking place in the future. It's just right there, and the urgency

Cuarón captures seems as real as anything set in modern day.

Cuarón has been building toward this for quite

some time. He has made excellent movies like Y tu mama tambien and Harry

Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban, the best and most cinematic of the Harry

Potter movies. But he shoots himself into the stratosphere with Children of Men.

He strikes a delicate balance here, too - the film's art direction is phenomenal,

realistically creating a future that looks both familiar and out of reach. The sensory

output of this version of the future is reminiscent in some ways of Minority

Report, only more gray, reflecting the bleak, pessimistic feeling that has

permeated, presumably, the entire world by this point.

Cuarón has been building toward this for quite

some time. He has made excellent movies like Y tu mama tambien and Harry

Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban, the best and most cinematic of the Harry

Potter movies. But he shoots himself into the stratosphere with Children of Men.

He strikes a delicate balance here, too - the film's art direction is phenomenal,

realistically creating a future that looks both familiar and out of reach. The sensory

output of this version of the future is reminiscent in some ways of Minority

Report, only more gray, reflecting the bleak, pessimistic feeling that has

permeated, presumably, the entire world by this point.

But amid all the despair, he finds the hope and the heart, without ever making it

feel like dramatic manipulations. His film has us in a gut-wrenching emotional

stranglehold, as the very real possibility of death surrounds Theo and Kee even as

our hope at their success grows. Clive Owen - finally starting to get starring roles

after years of going unfortunately under the radar - has never been better, and

Michael Caine, going against type as the film's comic relief, is brilliant as the

cynical old eccentric who delights in telling depressing but hysterical jokes.

It's hard enough for a film to succeed in one area, but when a film works on as

many levels as does Children of Men, it's an astounding accomplishment.

Somehow, the film is depressing, emotionally draining and full of hope all at once.

Cuarón and his screenwriters never pull a punch, and they have crafted the best

film of 2006.

Read more by Chris Bellamy